Over The Waves: SS Princess May

The Canadian Pacific Railway had been expanding its range since it’s creation in 1881, increasing their portfolio to include both railways and steamships ,and creating a way from someone to travel from Liverpool, UK to Japan, China, or Hong Kong without ever needing to change carriers. In 1901, they purchased the Canadian Pacific Navigation Company and added West Coast coastal ships to their list of services. This new division, the Canadian Pacific Railway Coast Service, sailed a fleet of “Princess” ships from Vancouver, BC to Skagway, Alaska. One of these ships is the one whose story we’re looking at this week – the SS Princess May.

Nationality: Canadian

Length: 76 metres

Beam: 10 metres

Weight: 2100 tonnes

Depth: 5 metres

Year: 1888

The Princess May began her career under a different name, and different company. Initially christened the SS Cass, she and her sister ship the SS Smith were built by Hawthorn, Leslie & Company, Ltd. of Newcastle-upon-Tyne for the Formosa Trading Company. With coal-fired boilers and two triple-expansion steam engines, she promised to be the passenger and supply workhorse that Formosa was looking for.

The SS Princess May. Image from the Vancouver Archives.

Instead of seeing service in Canada, Cass and Smith spent a bulk of their career in Taiwan. The Cass went through a series of name changes, including SS Arthur, SS Ningchow, and SS Ha-ting. It was under the latter that, in 1901, she was sold to the newly formed Canadian Pacific Railway Coast Service. CPRCS needed a fast, strong ship to meet the demands of service to southeastern Alaska, but they didn’t want to wait for a brand new ship to be built. Ha-ting was delivered, renamed the SS Princess May, and set on her new commuter route between Vancouver, British Columbia and Skagway, Alaska.

Working alternating weeks with the SS Islander and later the SS Princess Royal, the Princess May took to her new assignment without incident at first. The ships provided service not only to their two main ports, but to many small mining, fishing, and lumber communities that dotted the coasts of Alaska and British Columbia. In 1906 she was given a refit which saw her cabins enlarged and updated, as well as her superstructure rebuilt. With a fresh coat of paint as the finishing touch, she was back in the water by 1907.

Images like this one were very popular angles of the SS Princess May. Image from the Vancouver Archives.

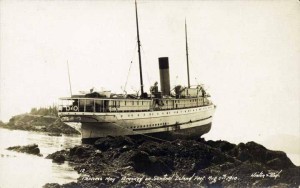

On August 5, 1910 under the command of Captain MacLeod, the Princess May steamed slowly away from the harbour in Skagway. A thick, heavy fog had settled along the Lynn Canal, so Capt. MacLeod kept his ship at a speed of 10 knots, hoping that it would clear. Much to his surprise, near the north end of Sentinel Island, Alaska, the ship shuddered and jumped as she ran aground on the rocks.

Princess May was equipped with a wireless set, but unfortunately it was hardwired into the ship’s main power, and didn’t have an auxiliary battery (this wouldn’t become standard practice until the wreck of the RMS Titanic two years later). Once the engine room began to flood, the ship went dark, and with it went their wireless communication. The wireless operator, a man named W.R. Keller, sprang into action. He rushed down into the engine room and managed to find a way to activate the wireless’ battery, giving him enough power to send out a distress call before the engine room completely filled with water.

SS Princess May. Image from Wikipedia.

In the meantime, the captain had begun abandoning ship. Lifeboats were lowered into the water and all 80 passengers and 68 crewmembers were able to make it ashore safely. There is also a story that a shipment of gold had been on board, and that this was removed and brought ashore for safekeeping. All the while, the tide continued to push the ship further onto the rocks, wedging her into place with her bow raised slightly out of the water. Of course, when the tide finally went out, she looked like this...

The wreck became a popular spot for photographers, and copies of their images and sold all along the West Coast. The Princess May was left stuck while her owners tried to figure out what to do with her. The damage was extensive, but not irreparable. She had damage to over 120 of her hull plates, her engine rooms were flooded, and she couldn’t move under her own power. CPRCS hired two salvage tugs – the Santa Cruz and the William Jolliffe, and constructed some temporary structures to aid in the repairs. After some hard work and a few failed attempts, the Princess May floated free on September 3, 1910, and was towed to port.

During her repairs, the CPRCS decided to change the Princess May from coal burning to oil, making her the first oil burning ship in their fleet and one of the most efficient. She continued to serve her Alaska-British Columbia route until she was sold to a steamship company in 1919 and transferred to the Caribbean. She spent the rest of her career in the warm southern waters, and was finally retired in the 1930s.